Balls and Walnuts

more than you ever wanted to know

It snuck up on me

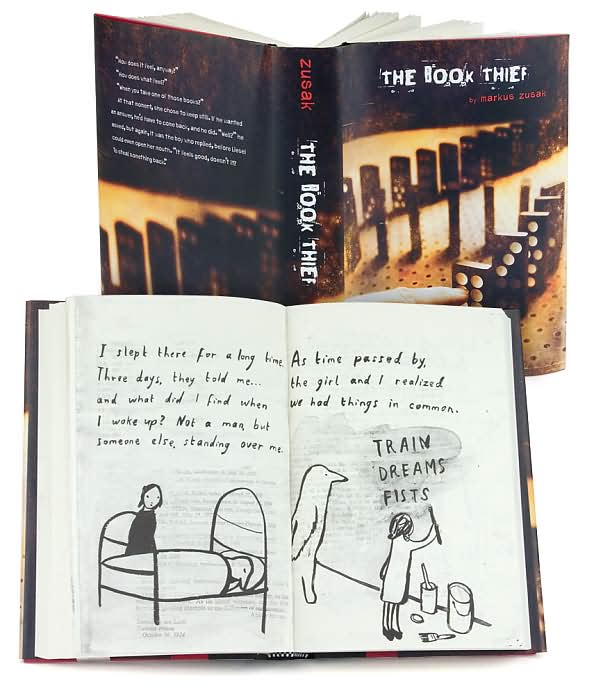

The Book Thief

by

Markus Zusak

The Book Thief makes me think of so many things: of being ten, having to write a book report for English, and thinking of nothing better than, “This book was really good. You should read it”; of being a Jewish kid growing up in the 60s and 70s, getting force-fed the Holocaust to the point that I couldn’t take it any more.

All right, already, I wanted to tell my Hebrew School teachers. I won’t forget.

I didn’t forget, but neither did I watch any Holocaust movies or read any Holocaust books. It took me thirty years to risk it — I read Elie Wiesel’s Night Trilogy two or three years ago, and I only did that because I was so impressed by Wiesel’s Wise Men and Their Tales. (For my more spiritually inclined readers, check out Wise Men. It’s a fascinating, unconventional look at several Old Testament figures.) I still try to avoid most WWII/Holocaust fiction, but I decided to give The Book Thief a chance after a commenter recommended it at Bookseller Chick’s place. Not only that, but an elderly woman saw me pick it off the shelf at Barnes and Noble, and praised it to the skies.

The Book Thief is the story of Liesel Meminger, a nine-year-old German girl growing up during World War II in Hitler’s Germany. Liesel steals her first book, a manual on gravedigging, soon after her younger brother’s funeral. She cannot read, let alone write, but the book becomes her most valued possession. As the title suggests, it’s not her last brush with thievery.

Liesel is sent by her mother to live with Hans and Rosa Hubermann. So many wonderful characters in this book — the Hubermanns, Liesel’s friend Rudy (a boy who idolizes Jesse Owens so much he once smeared himself with coal dust and raced himself on the local track), the mayor’s wife, and Max, a Jew in hiding. Also Death, who narrates the novel and becomes a surprisingly empathetic character.

This book makes me think of beef bourguignon. In beef bourguignon, each separate ingredient is pampered to perfection. What I’m trying to say is, The Book Thief is a stew of superb characters, but it’s a stew for an epicure.

And it snuck up on me. I stayed with it for the first two hundred pages because Zusak knows how to write and I found his characters interesting. We’re all so jaded these days. If we’re not hooked by the first page, we move to the next book in the TBR pile. Zusak’s opening hook (Death-as-narrator) felt gimmicky to me, but his writing ability kept me turning pages.

Somewhere around page two hundred, the book choked me up. Damn! How did that happen? I realized I cared about Zusak’s characters. Deeply. I wasn’t just reading it to admire the writing; I really wanted to know what would happen to these people. Since the era was Nazi Germany and Death was my narrator, I figured their fates couldn’t be too rosy.

FYI, even though I sniffled all through the last sixty pages, the ending is not a TOTAL bummer. Don’t avoid this one because of some odd aversion to sad books. You’d be missing a fine story indeed.

D.

Okay, I put it in my Zooba queue. I’m trusting you–if I end up horribly depressed afterwards, I’m sending you the therapy bills.

I picked this up recently, too, based either on Bookseller Chick’s post or maybe Keishon (Avid Reader). The narrative style interested me and Death-as-narrator, too, but I’m bogged down at about page 50. I keep reading the same 5-10 pages and can’t get past them. I even skipped to the last page and read the last line, which I seldom do — it has me hooked. I want to get to the last line the normal way, by reading all the pages that come before it, so I can understand why the last line is and what it means (other than the obvious), but I’m stuck! Ugh. 🙁

Darla, it’s about survival and growth under the worst possible circumstances. I think a reader can come away from it with a hopeful feeling, but it’s more complex than that.

JMC, yeah, I did the same thing! That ending line really kicks ass, doesn’t it? My advice, stick with it if you can. Around page 50, I was thinking, “This is pointless. Zusak doesn’t have anything new to say. This is just another WWII story, kind of like Anne Frank’s Diary but from a German POV. Bleh.” And yet his writing kept me going — and my early impression was incorrect.

[…] But the emotion began and ended in me. The movie was merely a prompt. Unlike The Book Thief, which touched me because I cared for the characters, Everything is Illuminated achieved its pathos through a Spielbergian plucking-of-heartstrings. As for the characters, only Eugene Hütz’s Alex felt both three-dimensional and comfortably human. Jonathan is a paper-thin neurotic. Alex’s grandfather — a character with enormous potential for drama and poignancy — exits in so baffling a manner as to undermine the entire film. […]

[…] And he’s such a talented author, too. As with The Book Thief, Zusak had me caring deeply for his characters: his protagonist, a slacker taxi driver named Ed Kennedy, Ed’s smelly dog the Doorman, and his friends — Ritchie, Marv, and Audrey, with whom Ed is deeply and hopelessly in love. Ed’s life is over at 19. He wants nothing more out of life than what he has and he doesn’t have much. […]