Balls and Walnuts

more than you ever wanted to know

Fictional characters adrift in the uncanny valley

Think about the times you’ve wanted to scream at a character in a book or movie, “No, that’s all wrong!” I’m not talking about characters who, in the interest of the plot, seem to have had their brains replaced with tapioca. I’m referring to those times when a character who felt so real to you a moment ago now . . . doesn’t. The former situation is all too common, because lazy writing is everywhere. Author Staci McLaughlin at The Ladykillers suggested two reasons for The Stupid Move: the author may want to heighten the suspense (as in Alien, when the crew insists on splitting up), or she could be stubbornly wedded to her writing. Laziness either way, really.

The latter situation may be a unique problem of good writers. How can you leave a reader or viewer in open-mouthed shock at your* criminal lapse of judgment if you haven’t created a convincing character in the first place? You can’t. You have to have the skills to create a living, breathing, fictional being before you can make the error of turning that being into something not quite human. If you make that slip, if your character says something he’d never say, or does something he’d never do, or fails to say or do something the reader expects him to say or do, then he has just fallen into the uncanny valley.

If you peruse that Wiki link, you’ll learn that this idea of the uncanny dates back to a 1906 essay by psychiatrist Ernst Jentsch. But “uncanny valley” has its origins in the work of Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori. In an essay published in 1970, Mori proposed that “as the appearance of a robot is made more human, a human observer’s emotional response to the robot will become increasingly positive and empathic, until a point is reached beyond which the response quickly becomes that of strong revulsion. However, as the robot’s appearance continues to become less distinguishable from that of a human being, the emotional response becomes positive once more and approaches human-to-human empathy levels.” (Original article here; quote thanks to Wikipedia.)

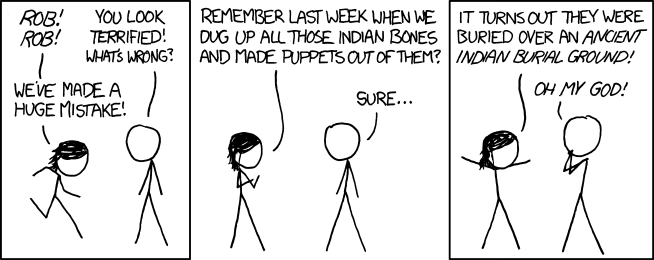

Shorter version: we like creations that are kinda sorta human (think Pikachu, or even a happy face symbol), and we like humans of course, but we’re creeped out by creatures that are almost, but not quite human. Case in point:

In this case, the fall into the uncanny valley has been perpetrated by the filmmaker to evoke a sense of horror. Donald Sutherland has been our hero throughout the movie, and he’s a really likable guy. When he first looks at Veronica Cartwright with such a serious expression, our first thought is probably, “Oh, crap, look behind you!” You don’t expect the danger to come from Sutherland. And that sense of danger comes entirely from the wrongness evident in Sutherland’s subsequent expression.

The “valley”, by the way, refers to a function Mori described in his original article:

Here, the y-axis denotes our emotional reaction, positive to negative, while the x-axis denotes familiarity of appearance. Again, it’s that close-but-not-quite territory that triggers our sense of squick. If you have four minutes to spare, here’s an excellent treatment of the topic:

For writers, the key is to recognize this phenomenon and use it, either as a tool (see Invasion of the Bodysnatchers, above, or numerous examples in John Carpenter’s The Thing), or as a cautionary tale. Seems a shame to invest all of your talent and effort in character creation, only to piss it all away with one misstep.

Note that your job as a writer is easier than the job of an animator or robotics engineer. Their constructs exist in the real world, while yours exist in the mind of the reader. If you nail “life-like” closely enough, your readers will carry you past the valley to the peak beyond. Same goes for screenwriting: assuming your character looks human (or, if alien, looks the way your viewers expect him to look), if his actions and words maintain a certain logic and consistency, the viewer will leap the valley and believe in your character’s essential humanity (yup, even for aliens, if we’re being honest about it). You almost have to work overtime to screw this one up.

If I may pontificate for a sec, it’s worth remembering what John Gardner said about fiction: that it is a consensual dream. Similarly, Ford Madox Ford, in discussing the ending of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, wrote,

The last paragraph of a story should have the effect of what musicians call a coda — a passage meditative in tone, suited for letting the reader or hearer gently down from the tense drama of the story, in which all his senses have been shut up, into the ordinary workaday world again.

That return to the workaday world should occur at the ending, needless to say, and should ease the reader back. Sudden slips into the uncanny valley are like the college roommate who flips on the room lights and shouts “Rise and shine” while you’re still lost in that lovely, lovely dream.

D.

*Yes, your lapse in judgment. His first thought might be, “Guinevere would never slobber over Lancelot’s codpiece like that. She knows those things rust, and damn it, that woman has a respect for fine armor.” But his second thought would be, “Who the hell wrote this tripe?”

Interesting post. Another angle on the uncanny valley is to think of how putting two waveforms together that are a little bit off creates beat harmonics, while two waves that are opposite just cancel out. It’s the little differences that are more irritating.

Sometimes when in real life a person does something unexpected, it can lead to a richer view of the person. I remember finding out a friend of mine smoked and being quite shocked and it sort of realigned my view of him. We’d been friends for a while and it seemed out of character. I suppose the same could happen in fiction, if the character does something unexpected/out of character, but then the author develops that side of things.

It’s a question of intention. If the author is aware of what he’s doing, great — he’s making good use of the uncanny valley. It’s that unintentional “whoops” that bugs the crap out of me when I’m reading an (otherwise) good book. (TV tropes, by the way, has a good listing of intentional uses of the uncanny valley. Unfortunately, they haven’t cataloged the screw-ups. In writing this post, I tried to remember specific instances and couldn’t. Oh! Perhaps the moment at the end of The Lovely Bones (SPOILER) when the protagonist has a poltergeist moment and revenges herself on her killer. THAT was totally out of left field, clearly put there to gratify the author. Only problem with this example — I didn’t like the author’s writing, nor did I think The Lovely Bones was a good book. Oh, well.)