Balls and Walnuts

more than you ever wanted to know

A B&W redux

I had been trying to think up a fun topic for tonight’s post when I remembered Kakabekia. Then I had the thought, “Kakabekia is such a neat story, I’ll bet I’ve done this before,” and crap, I was right! When I found my old post — one of the Thirteens — I had so much fun rereading it that I decided to post it as a redux. Hopefully y’all will have forgotten it as well as I had, all the better to re-enjoy it.

A note on the Kakabekia story: I learned about this organism in a biology class I took during med school. Early Evolution of Life, or some such. I remember I wrote a pretty cool term paper for that class, suggesting that within the genetic code of most life on earth (not all life forms share the same code, although all codes are quite similar) one could demonstrate evidence that the code itself is a product of selection. My teacher liked my term paper so much he suggested I write it up for publication, which I never did. This would have been, oh, 1988 or 1989? And guess what, on that Wikipedia page I just linked to, there’s a link to a paper published in 2003 making just that point.

I can’t tell you how many times this happened to me back in those days. I would have a great idea — perhaps something theoretical, like this genetic code bit, or perhaps something technical, like a way to fish for genes encoding promoter-binding proteins. Someone in authority would say, “Hey, good idea, get to work on it,” and I wouldn’t. There were always other things to do. My ideas were top notch, but my ambition, or perhaps my sense of perspective, insight into what was REALLY important, whatever . . . sucked.

Sorry. I didn’t mean to turn this into a kvetchfest. I was meant to be a doctor, right? Not a scientist. Or, if I was meant to be a scientist, it was only after skipping over all that dull gruntwork as a grad student or post-doc. Yup. Go straight to the finish, have my own R01 and scads of my own post-docs and grad students doing my bidding, turning my fine ideas into realities. Shame life doesn’t work that way.

Below the fold: thirteen cool microorganisms. (And, hey! It’s even Thursday!)

Just one question: where did I find time, in the old days, to write such detailed posts?

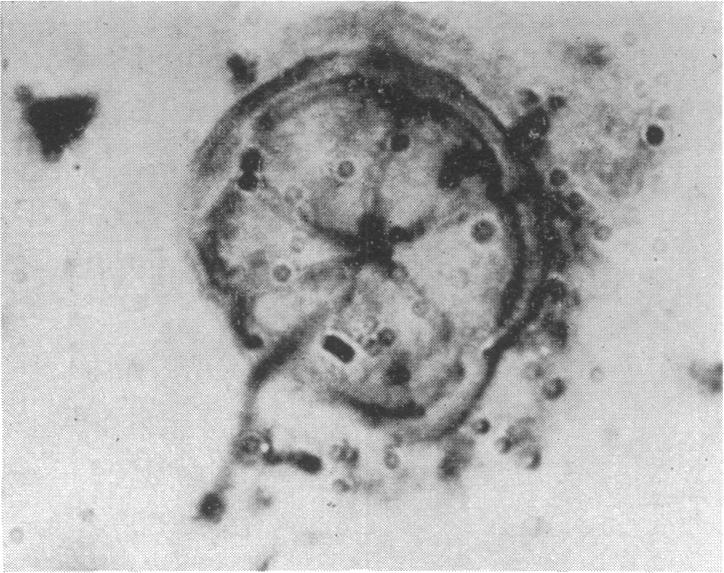

1. We’ll begin with one of the most interesting critters on the planet, Kakabekia barghoorniana.

One of Charles Darwin’s more troublesome problems was the absence of a pre-Cambrian (approx. 550 million years ago) fossil record. The “missing Pre-Cambrian life” problem remained a mystery for over a 100 years, until scientists in the 50s and 60s discovered microfossils — fossilized remnants of ancient microorganisms. We now have a fossil record dating back 3.5 billion years.

One of the earliest findings (in the mid 1950s) was that of Kakabekia, an umbrella-shaped creature which was, at the time of its discovery, unlike anything else known on the planet. Flash forward to the mid 1960s, when an American scientist, Sanford Siegel, collected soil samples in Harlech, Wales, from an area that had been used as an open-air latrine since Roman times. When he cultured the soil in an ammonia-rich environment, he grew Kakabekia-like organisms, which he dubbed Kakabekia umbellata Barghoorn (Barghoorn, in honor of the man who discovered the fossil Kakabekia). Siegel’s Kakabekia may well be descendants of a life form which existed two billion years ago!

Back then, Earth’s atmosphere was ammonia- and methane-rich, not oxygen-rich as it is today. The existence of an ammonia-loving creature has stimulated speculation that there may, indeed, be life in other harsh environments — such as in the atmosphere of gas giants like Jupiter. Organisms that love atypical conditions are known as extremophiles. We’ll get back to them in a moment.

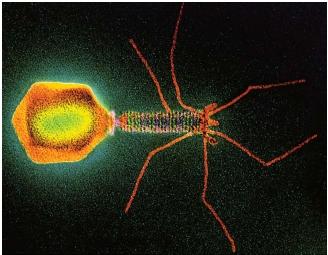

2. T4 Bacteriophage. Most every college biology major, and some who only dabble in biology, eventually discover the T4 bacteriophage. Bacteriophages are viruses which infect bacteria — E. coli in particular, which as you may know, is an important organism both for normal bowel health, and in some cases, life-threatening disease.

2. T4 Bacteriophage. Most every college biology major, and some who only dabble in biology, eventually discover the T4 bacteriophage. Bacteriophages are viruses which infect bacteria — E. coli in particular, which as you may know, is an important organism both for normal bowel health, and in some cases, life-threatening disease.

This wicked-looking fellow has “legs” which can sense and bind to an appropriate bacterium’s cell wall. The phage then acts like a hypodermic needle, injecting its genetic material (contained in the “head”) into the bacterium. The viral DNA commandeers the bacterium’s cellular machinery, turning it into a factory to make more phage. When the bacterium is chock full of virus, the bacterium bursts open, unleashing infective particles on all the other unfortunate bacteria in its environment. For an animation and more information on the T4 bacteriophage, check this site.

3. Stephanodiscus, another “living fossil”.

Here’s another cool picture. From that link,

Diatoms are a group of microscopic algae that have a cell wall made of biologically produced glass. The glass cell wall is what we are seeing in these pictures, or micrographs. Stephanodiscus niagarae was discovered in 1845 and described by the German diatomist Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg from material collected at Niagara Falls. Today this species is still common in many temperate lakes in North America.

Want to learn more about diatoms? They have their own home page (and you, too, can play “guess the mystery diatom”!)

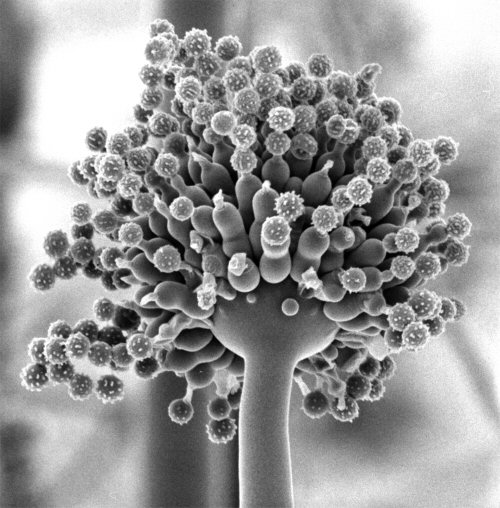

4. Aspergillus niger.

Isn’t it pretty? This is black bread mold. As a kid, I used to steal slices of Wonder Bread, take them out to my “lab” (then, a wooden work bench at the back of our garage), and find some way to keep the bread dark and damp. I had a chemistry set, too, and I would sprinkle different chemicals on the bread in the hopes of growing something different each time. No go — all I ever got was black bread mold or green bread mold. Not very exciting.

Nor is it very exciting when I have to clean this crap out of peoples ears, or worse, out of their sinuses. Usually, this is no more than an annoyance, but in immunocompromised patients Aspergillus can be deadly.

5. Tardigrade, another extremophile.

Another cute microorganism. Tardigrades, also known as “water bears” or “moss piglets,” are, at 1 mm or less, the giants of this Thirteen. Although they live all over the world, they qualify as extremophiles because (quoting the Wiki)

[they] are able to survive in extreme environments that would kill almost any other animal. They can survive temperatures close to absolute zero, temperatures as high as 151°C (303°F), 1000 times more radiation than any animal, nearly a decade without water, and can also survive in a vacuum like that found in space.

Forget about cockroaches ruling the world after WW III. The next sentient life form will be descended from water bears.

6. Plankton.

Plankton are the wanderers of the sea. Although some have the ability to swim, most are swept along by ocean currents. They are defined by their style of living; plankton span nearly every living kingdom, including plants, animals, bacteria, and archaea. They span a huge size range, too — not all plankton belong in a Micro Thirteen.

Wikipedia has a concise treatment of the debate over the origins of syphilis. The old school (and moderately racist) theory holds that Columbus and his crew brought syphilis back to Europe, having acquired it from New World natives. The “Pre-Columbian” evidence is persuasive, however, and includes abundant skeletal evidence (here, for example).

Early treatments for syphilis included mercury (“A night in the arms of Venus leads to a lifetime on Mercury”), the arsenic-containing antibiotic Salvarsan, and fevers induced by infecting the patient with malaria. The first truly effective treatment of syphilis was, of course, penicillin.

The T. pallidum genome was sequenced in ’98. At 1,138,006 base pairs, it’s one of the smaller bacterial pathogens.

Oh, and you know how penicillin was THE drug for syphilis for years and years? Drug resistant strains are spreading. So, don’t get too cocky.

8. Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Where would we be without Brewer’s yeast?

Answer quickly: yeast belong to which biological Kingdom?

Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been used in baking and brewing for thousands of years. According to Wikipedia, “Archaeologists digging in Egyptian ruins found early grinding stones and baking chambers for yeasted bread, as well as drawings of 4,000-year-old bakeries and breweries.” In those days, beer was an important staple — “liquid bread.” I suspect ancient beers were more nutritious and less alcoholic than modern beers, which do not seek to nourish.

Answer to the question: Fungi. Yes, yeast is a fungus, and when you drink beer, you’re drinking fungus juice. Old Fungi: Taste As Great As Its Name.

Speaking of fungi . . .

9. Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, a waterborne fungus responsible for chytridiomycosis. Why should you care? Because this illness is causing a massive, worldwide frog die-off, that’s why. AND I LIKE FROGS!

9. Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, a waterborne fungus responsible for chytridiomycosis. Why should you care? Because this illness is causing a massive, worldwide frog die-off, that’s why. AND I LIKE FROGS!

How does chytridiomycosis kill frogs?

The fungus is thought to kill frogs either by releasing fatal toxins that are absorbed by the frogs semi-permeably skin, or through damaging the skin so badly that the frog’s water and electrolyte balance as well as their respiration are affected. The fungus also damages the nervous system, affecting the frog’s behaviour.

And how can I tell if my frog is infected? (same link)

- loss of skin from the arms, legs and belly

- are sluggish, and have no appetite

- trembling

- sit out in the open, not protecting themselves by hiding

- have their legs spread slightly away from themselves, rather than keeping them tucked close to its body.

Infected captive frogs can be treated with a dilute solution of the antifungal drug itraconazole. To my knowledge, no one has figured out what to do about the infection devastating wild populations around the world.

Here’s a link to more information on the debate over the global amphibian die-off.

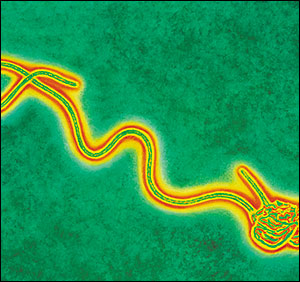

10. Ebolavirus. It kills up to 90% of its victims. Viruses don’t get much more bad-assed than that.

Ebola virus hemorrhagic fever usually begins with the sudden onset of fever, fatigue, muscle aches, and headache, followed by sore throat, vomiting, diarrhea, and a rash. The disease can progress until the patient becomes very ill due to severe bleeding which causes kidney problems, liver problems, and shock.

Funny thing happened when I searched for info on Ebola. I found a Free Republic article claiming that some biologist, at a meeting in Texas, advocated unleashing Ebola worldwide to reduce the world population by 90%. I’ll bet those freepers ate that story up like rats eating chocolate chip cookies.

11. Filarial nematodes, the critter which causes elephantiasis. You know, I may have lied about water bears being the biggest creatures on this Thirteen. Nematodes are probably a bit bigger. Anyway, these critters can clog the lymphatic vessels in any part of the body. This leads to accumulation of lymphatic fluid in the afflicted part, with gross enlargement and resultant dysfunction.

11. Filarial nematodes, the critter which causes elephantiasis. You know, I may have lied about water bears being the biggest creatures on this Thirteen. Nematodes are probably a bit bigger. Anyway, these critters can clog the lymphatic vessels in any part of the body. This leads to accumulation of lymphatic fluid in the afflicted part, with gross enlargement and resultant dysfunction.

This is primarily a disease of poor, tropical people; over 120 million are afflicted. The Global Alliance to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis is on the job, but I’m not sure I believe their numbers. They claim, “In 2005 381 million people received the necessary drugs.” Not sure how to square that with the 120 million figure.

Wikipedia is kind enough to note that elephantiasis is NOT the same as the Elephant Man’s disease. Joseph Merrick suffered from Proteus Syndrome, a congenital disorder.

12. Bioluminescent algae. Enjoy the beauty of phosphorescent surf . . . and then read all about it.

13. Archaea

When I was a kid, I figured that science was sufficiently on top of things that all of the major Kingdoms of life had been identified. Boy, was I wrong. I’ve lost track of how many times the Kingdoms have been rearranged. And good heavens, when did they first invoke a level of classification above Kingdoms — AKA Domains?

Yeah, apparently Bacteria aren’t a Kingdom nowadays. They’re a domain, along with the Eukaryota and the Archaea. Eukaryota, that’s like you and me and the rats in my attic and the mites in my mattress; Bacteria, that’s like the crap between my teeth and the crap in my, um, crap. But I suspect a few of you may be unfamiliar with the Archaea.

Archaea are microorganisms who, like bacteria, lack proper nuclei, but who nevertheless have many features in common with eukaryotes. I first learned about the Archaea when I studied extremophiles, and indeed, that’s how they were first discovered. But according to Wikipedia, they “have since been found in all habitats and may contribute up to 20% of total biomass.”

Guess I shouldn’t be too surprised; we didn’t know about dark matter when I was a kid, either, and that stuff is everywhere.

D.

Been there, done that. Or, rather, been there, didn’t do that too.

I wrote a skit back in high school for a writing class, and the teacher suggested I submit it to SNL. I got so far as to look up contact information, and then there were other things to do…

i miss the days of TT. le sigh. i put a reminder on my whiteboard that says “Remember to LJ!” and haven’t yet…so effective…:-/