Balls and Walnuts

more than you ever wanted to know

- About

- All Change

- Big pix

- Dormies

- Ear, Nose, Throat, and Soul

- Heaven on Earth

- Karen’s memoriam . . . booklet and eulogy

- Lyvvie’s email

- Magic Schoolbus does your nose and throat

- Nest: scene one

- Sex and the Single Wendigo

- Sprouts

- The Mechanic

- Two Birds, One Stone

- Excerpt: Gator and Shark Save the World

You Don’t Know Jack

Believe it or not, in med school we did receive instruction in medical ethics. Our teacher was a minister, if I remember correctly, but he usually did not have much of a judaeochristian bias — at least, none that I could detect at the time. One day, he talked to us about euthanasia, and while sympathetic to the cause of euthanasia’s proponents, he felt certain that doctors had no business practicing euthanasia. “We need another professional specialty altogether,” he said. “Call them thanatologists.”

The two things I remember from that moment: the uncannily bright grin of one of my classmates, a fellow we’d nicknamed Mickie Mouse for his uncannily bright grins, and who would eventually go into psychiatry; it was as if the clouds had parted and he had looked upon the face of God. Like he had found his home. Sometimes I wonder what he’s up to*.

The other thing I recall: a loud and persistent thought. Why isn’t this our domain? It’s all a matter of how you view doctors. If our role is to keep people alive, then yes, euthanasia is a clear conflict of interest. But if our role is to relieve pain and suffering, then euthanasia should be part of the job.

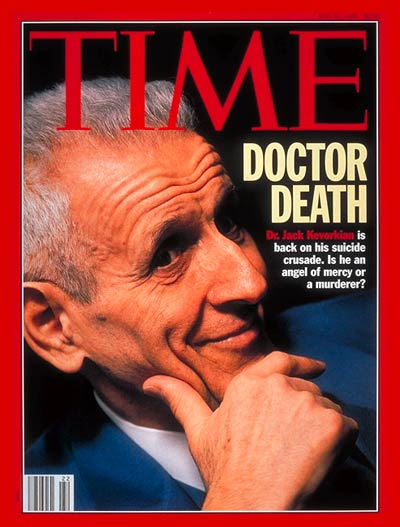

About this time, the late 1980s, Jack Kevorkian was just getting started in his role as “death counselor,” soon to be death facilitator, eventually to be known to the media as Dr. Death. The media loved to portray the man as a ghoul. Sometimes I suspect that he reveled in this caricature; his artwork, which could best be described as “fitting for the Night Gallery,” would do nothing to destroy this image.

Knowing Time Magazine, I wouldn't be surprised if they had picked murderer.

While Kevorkian initially acted as a facilitator, he ceaselessly pushed the envelope. As long as he served as facilitator and not prime actor, he was judicially unscathed, thanks to the craft of lawyer Geoffrey Fieger and the sympathies of the juries. (When people are forced to confront the prospect of their own deaths, few would not want the option of a painless passing.) But when he himself administered the euthanasia drug to an ALS patient and then arranged for the videotape to be broadcast on 60 Minutes, the D.A. went after him. Kevorkian unfortunately represented himself in this case, and was ultimately convicted of second degree murder. He was ultimately paroled in 2007 after a little over 8 years in prison.

You Don’t Know Jack (HBO) is a wonderful bit of docudrama, not to be missed. Susan Sarandon stars as Hemlock Society member Janet Good, John Goodman as Kevorkian’s friend and assistant Neal Nicol, and Al Pacino plays Kevorkian himself. And while I like Pacino in just about anything he does, I have to admit that lately, Pacino plays Pacino and it’s rare to see him play anyone else. But in You Don’t Know Jack, Pacino lives and breathes Kevorkian. If you’ve ever watched Kevorkian on TV (and if you haven’t, I’d be surprised if he isn’t well represented on YouTube), you’ll find the resemblance striking. Also remarkable casting: Danny Huston as lawyer Geoffrey Fieger. I had to google “Geoffrey Fieger” to make sure he wasn’t playing himself.

I can’t praise this one enough, people. It’s a thoughtful, albeit biased analysis of the issue of doctor-assisted suicide. If you’re looking for a character in this film who can provide a cogent argument against euthanasia, keep looking**. Much like its subject, the movie has an agenda. But it was entertaining, too — funny, poignant, and above all a showcase of terrific acting.

D.

*Ach, what a disappointment. Just googled the man. He’s a successful molecular biologist at U of Chicago . . . not a thanatologist.

**Really, the only argument that comes close to being persuasive is the possibility for abuse by next of kin; but abuse to the point of death can occur in many and varied ways, from neglect to outright physical harm, and the law is there, ready to punish the offender. Euthanasia, since it is such a public act — it must ultimately pass muster with a coroner, I would think — could be easily regulated to greatly reduce the possibility of such misuse.

4 Comments

Find it

Blogroll

- Beth

- Blue Gal

- Charlene Teglia

- Chris and Dean

- Crystal

- dcr, the one, the only

- Erin O’Brien

- Fanatic Cook

- fiveandfour

- Gabriele

- If I Ran the Zoo

- Indecision 2008!

- jmc

- Kate Rothwell

- Kris Starr

- Lyvvie

- Matt’s recovery blog

- Mike Imlay

- Paperback Writer

- Pat Johanneson

- Raw Dawg Buffalo

- Science Blogs

- Shaina

- Shelbi

- Smart Bitches

- Steve Bunche

- Steven Pirie

- Tam’s blog

- The Amanda Files

Archives

Meta

Categories

Pages

- About

- All Change

- Big pix

- Dormies

- Ear, Nose, Throat, and Soul

- Excerpt: Gator and Shark Save the World

- Heaven on Earth

- Karen’s memoriam . . . booklet and eulogy

- Lyvvie’s email

- Magic Schoolbus does your nose and throat

- Nest: scene one

- Sex and the Single Wendigo

- Sprouts

- The Mechanic

- Two Birds, One Stone

I’ve occasionally wondered about this. How would I handle these issues if I were a doctor? I don’t think I could perform abortions, and I don’t think I could perform euthanasia, either.

I think your old ethics prof was right. Thanatologists would be part of the palliative care branch.

I don’t have a problem with it. Not that I’ve ever been in a position to be the one to prescribe the necessary meds, though; primary care docs seem to be the ones who get that task. But I don’t think I’d have any trouble, since I see my job as one of improving function and relieving pain, or at the very least relieving pain. I find the “extend life whatever it takes” philosophy to be offensive, since extending life often requires a terrible degradation of the quality of life. If that’s what the patient wants, fine, but more often than not (as with my father-in-law, who died several years ago of pancreatic cancer), the patient makes his choice because of the wishes of a frightened spouse.

My dear brother had a catastrophic brain aneurysm and was left brain dead. As a family and at the uging of doctors, we decided to discontinue his life support. My father had advanced Alzheimer’s disease when it was discovered he had advanced pancreatic cancer. He died two days later but would have lasted much longer without the high doses of morphine adn other drugs he was given by his doctors. If those two examples qualify as euthanasia, then I’m all for it.

Discontinuance of life support by itself does not constitute euthanasia, and isn’t considered controversial. Kevorkian* makes the point that we’re asking these patients to die by starvation, which is hardly humane. And for those folks who are on respiratory support, death by suffocation is an even worse fate.

When high doses of morphine are used to ease the transition, this approaches (if not equals) euthanasia, and is, I suspect, a widespread practice. Withdrawal of life support usually goes hand in hand with this usage of morphine, so in practice I suspect few patients suffer from suffocation or starvation without the benefit of painkillers.

What made Kevorkian’s approach controversial is that his patients were not hospitalized and were not dependent on life support. They would, without his assistance, continue suffering for months to come. That led some people to see this as Kevorkian contravening God’s will, hence much of his opposition from the religious right.

*in the movie, and I would not be at all surprised if this is an accurate portrayal of his views in real life.